How an Iraqi VC thinks in 2023

Money isn't the problem.

Biography

Zahi Hilal is an Investment Manager at Iraq Venture Partners, one of the country’s first VCs. He previously served as a program manager at Berytech, a Lebanese entrepreneurship support organization based in Beirut.

Can you pinpoint the birth of the modern Iraqi startup ecosystem?

I like to segment the ecosystem’s “history” into three phases. There was no pivotal moment per se, but rather a succession of incremental improvements.

Phase 1 took place in the early 2010s. A lot of individuals were eager to create and kickstart a local startup scene. This led to the opening of co-working spaces (ex: Fikra Space) and the organization of events (ex: Startup Weekend). Baghdad, the capital, remains the ecosystem’s undisputed epicenter. From then on, the ecosystem grew very slowly until phase 2 started, around 2019.

Phase 2 saw international donors, who are omnipresent in the country, shift their focus from livelihood to reducing youth unemployment. One of the ways they decided to do so was through entrepreneurship support programs. This ushered in a proliferation of entrepreneurship support organizations (ESOs).

However, these ESOs were not properly equipped to foster tech, hyper-growth startups. Donor-funded programs’ KPIs resulted in propping up more SMEs than VC-ready startups.

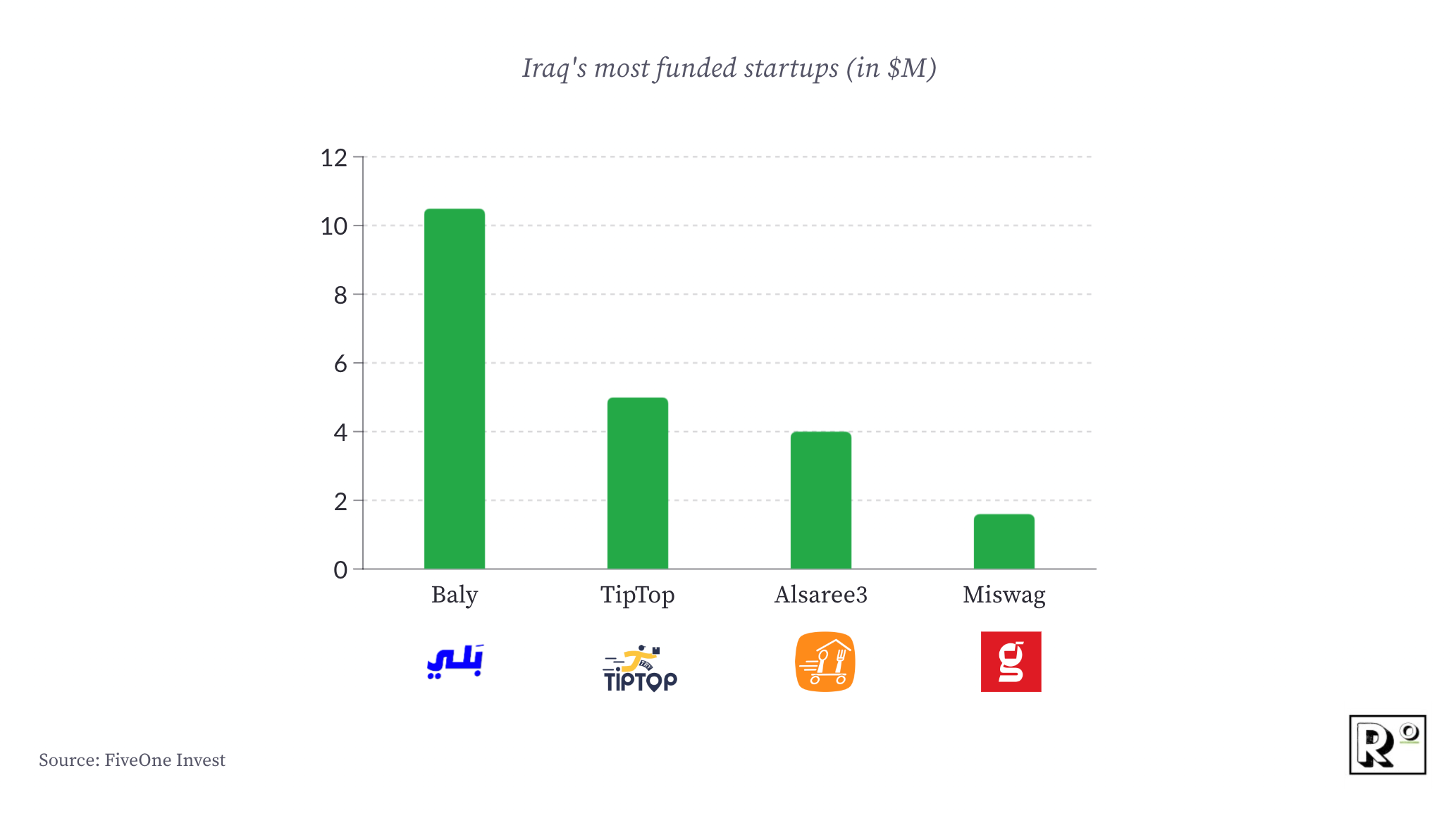

The startup ecosystem did get a nice boost in 2019 when Lezzoo, based in Iraq’s Kurdish region, became the first Iraqi startup to get into Y-Combinator. 2021 and 2022 saw some notable startups raising substantial rounds: Baly raised north of $10M, TipTop raised $5M, and Alsaree3 raised over $3M.

Well-funded foreign food-delivery startups such as Toters (from Lebanon) have also entered the Iraqi market and raised money on the promise of capturing Iraqi consumers.

This leads us to phase 3, which we are currently in. Donors are expected to scale back their support as other global humanitarian crises require attention. Entrepreneurship support programs have also evolved to require more contribution and commitment from the founders. In 2023, IFC (StartMashreq) and GIZ (CARP) are expected to launch new programs, which will replace direct grants with mechanisms that match the founder’s commitment to grow their business.

How do you explain the jump in VC funding in 2021 and 2022?

It’s important to note that most of the ecosystem’s funding has been captured by a handful of startups. Their common denominator is their focus on the food delivery and/or mobility sector. This could be attributed to Lezzoo’s traction as well as Talabat’s (UAE) and Careem’s (UAE) exits, making those sectors seem like the “low-hanging fruits” for investors.

While this does make for a good competitive environment, I’m eager to see more Iraqi startups solve other problems in education, healthcare, agriculture… The opportunities to do so are endless.

Can you talk about the Iraqi market’s fragmentation, and what it implies for startups?

The Iraqi market isn’t significantly fragmented. However, challenges to scale operations across the country can be attributed to 2 factors: limited funding and frictions between central Iraq and the semi-autonomous Kurdish region.

The semi-autonomous Kurdish region has its own government, court system, and law enforcement entities. This requires founders to treat expansion there as an expansion to a new market. With that being said, the main challenge to expansion remains the limited capital available to Iraqi startups.

The shortage of growth capital, necessary to fuel expansion, nudges founders to consolidate their market presence in the major city they start from. Baghdad, as the capital and home to a population of 10 million, thus stands as the hub for startup activity. Following closely, Erbil, the Kurdish region’s capital, assumes a secondary role. The shortage of Series A capital pushes founders to sacrifice growth for profitability while they opportunistically initiate expansion campaigns. This might create the perception of a fragmented market.

How can Iraq's oil wealth finally be leveraged to spur the startup ecosystem?

It’s a big challenge. The main channel to distribute oil wealth is through the public sector. Current governments in both Baghdad and Erbil are tackling corruption and clientelism, meaning there is still a long way to go before channeling Iraqi oil money to startups. Especially with proper transparency and compliance with international laws/regulations.

Currently, the best way for the ecosystem to leverage Iraq’s oil money is to upgrade physical and digital infrastructure. Central and regional governments are both implementing projects to enhance the transportation infrastructure, but more projects are still required to enhance the electricity supply and internet bandwidth.

There are some more “direct” public initiatives in the works, such as credit programs for SMEs implemented by the Central Bank of Iraq (CBI) and the Iraqi Private Banks League. The CBI recently announced a new endeavor to establish a dedicated bank for SMEs, the “RIYADA Bank for social development”. The CBI could also encourage the country’s banks to invest in Iraqi startups. We’re keeping an eye on it.

Is there also a way to get Iraq’s HNWI in on the action?

There are different shades of local HNWIs, so you have to be careful which ones you target. That being said, yes it is an opportunity. Iraqi businesspeople who have succeeded in the treacherous Iraqi market could bring massive value, both intellectual and financial, to local startups.

It takes time to pitch them the opportunity. They are mostly used to investing their money abroad, or in traditional sectors such as real estate. Convincing and getting them to invest in Iraqi startups is a marathon, but we’re running it.

What are the biggest obstacles to the ecosystem's development?

I think we have a lot to do in terms of regulation. I have a long laundry list:

- Taxation: Iraqi startups are taxed before they make money. This is negligible revenue for the government but can kill an early-stage startup.

- Ownership: Except in the Kurdish region, Iraqi law stipulates that 51% of Iraqi companies have to be owned by Iraqis. This evidently discourages international investors and founders.

- SAFEs: Iraqi law lacks convertible notes legislation. These are crucial for early-stage startup investments.

- IP: Our universities aren’t producing a lot of “market-usable” IP. This needs to change, as we have great talent.

On top of those, I think it would help to have a fund of funds of sorts, which could act as an “anchor” investor to local VCs. We could also imagine that entity matching investments from angel investors. $100M, a minuscule slice of the government’s fiscal budget, would already be a massive boon for the ecosystem.

Where do you see the ecosystem in 5-10 years?

First, it’s an interesting mental exercise to speculate on where today’s startups will be.

Regarding the ecosystem as a whole, IVP works with other stakeholders to seed and grow startups in untapped sectors in Iraq such as HealthTech, EduTech, CleanTech ….I believe as an ecosystem we should be shooting for 2030 KPIs of:

- 10-20 seed-stage deals per year

- 5-10 early-stage deals per year

- A couple of startups expanding to other markets outside Iraqi borders

- 1-3 exits with decent multiples for early-stage investors

The food-delivery sector will remain vibrant, as both local and foreign startups engage in fierce competition. I wouldn’t be surprised that, within the next couple of years, we see an exit there.

Talabat (UAE) is being seriously challenged by Toters (Lebanon) as well as local startups, and I believe they should acquire some of their competitors to fast-track their market expansion. It goes without saying that the acquisition of an Iraqi startup would be a great milestone for the ecosystem.

I would also keep an astute eye on Baly, Iraq’s most funded startup. They’ve raised on the premise of becoming Iraq’s super-app. They haven’t truly dominated any vertical yet. They face severe competition on the two seemingly “low-hanging fruits”, namely food-delivery and ride-hailing.

As already mentioned, the local food-delivery scene is crowded, and Careem and Obr (yes, the name is clever) are pushing into ride-hailing. The next couple of years will be crucial, with Baly either dominating these verticals or burning through its war chest with mediocre results to show for it.

For IVP, the general outlook for Iraq remains very bullish despite the challenges that it may face. We believe that the growth of aggregate capital invested in startups and the growth of high-caliber startups’ headcounts will scale in tandem, which will enable early-stage investors to invest at attractive multiples. This should translate into better prospects for above-average cash-on-cash exit multiples in the early 2030s.

The Realistic Optimist’s work is provided for informational purposes only and should not be construed as legal, business, investment, or tax advice.