An untold story of the Tunisian startup ecosystem

An exclusive op-ed by Ezzedine Cherif, former founder of Split, a Tunis-based carpool startup.

Biography

After studying accounting in France, Ezzedine Cherif returned to Tunis and joined IHEC Carthage in 2018 where he pursued studies in management. Realizing the enthusiasm students had for entrepreneurship combined with the lack of legal support in the country, he launched Startup Factory to support the administrative constitution of companies.

In 9 months, 70 projects were created using the platform. Ezzedine won the 2nd Moovjee prize for the student entrepreneur of the year and participated in the EL PITCH show. In 2019, he embarked on the challenge of giving his fellow students a transportation alternative to improve their transportation options: Split, a carpooling mobile app.

He is now Head of Growth at Oneshot.ai, based out of London.

Non-literate actors

The Tunisian startup ecosystem sometimes feels like a circus. The fact that a number of the ecosystem’s initiatives are run by people with dubious startup credentials substantiates the feeling. This makes progress inevitably complicated. Let’s start with one of the ecosystem’s cornerstones: incubators.

Due to the youth of the ecosystem, an overwhelming amount of Tunisian incubators are linked to foreign aid organizations, in one way or another. This is a characteristic shared across virtually every ecosystem on the African continent. Local investors’ reluctance to invest in the startup scene has left foreign aid organizations to foot the bill.

The result has been the rise of questionably effective incubators. Not because management has bad intentions or is incompetent, but rather because the people funding the incubator have no startup expertise. Indeed, foreign aid organizations aren’t known for their start-up proficiency. It has already been scrutinized in this publication.

This leads to cohorts of Tunisian founders hosted in these incubators to receive funding and advice that is out of line with startup best practices. So-called “mentors” at these incubators often have no startup experience themselves, rendering their contributions to the startups they mentor profoundly mediocre. Incubators investing $12K into a startup’s “seed round” arguably hurt the startup’s credibility more than it helps it, especially in the face of international investors.

By way of foreign aid organizations’ mandate, which in many cases is restricted to the country they are operating in, startups incubated by these structures also suffer from a severe lack of ambition.

It seems that foreign-aid-funded incubators have a hard time dissociating a VC-backable startup from a local SME.

Tiny and complicated local market

This local-focused attitude is highly detrimental to startups. The simple truth is that a startup thinking of Tunisia as the end-all-be-all is inevitably doomed to fail. The tiny market size means the potential scale is far too small to consider attracting proper VC funding.

Unfortunately, many founders and local investors are still stuck in that Tunisia-first mentality, when they should view the country as nothing more than a quick trial market before scaling internationally. Incubators that adopt their donors’ SME mentality share part of the blame.

However, even founders that properly treat Tunisia as a preliminary market face myriad obstacles before achieving the metrics required to raise an “international-door-opening” round.

Tunisia’s market size isn’t the 12 million people living there, but rather the less than half of those 12 million that own a bank account. The infamous Tunisian bureaucratic hurdles take away precious time from founders that should relentlessly be learning and iterating from their first Tunisian users.

When I was running Split, a carpool app I founded in 2019, it took me 6 months to register the company and 2 months to open a bank account. While 2 weeks could make the difference between my startup’s life or death, 3 or 6 months seem to be equivalent in the eyes of the Tunisian administrative machine.

To summarize what I’ve said so far: Tunisian incubators’ funding sources lead many founders to adopt an unfavorable “Tunisian SME” mentality which will inevitably block them from raising VC funding. And even for founders that are detached from that mental barrier, Tunisia is a highly complicated market to test in due to its tiny size and outlandish regulation.

Mentalities mismatch

The lack of proper startup literacy also applies to the local investor scene. The novelty of our country’s startup ecosystem, combined with the fact that exits are far from abundant, results in local “angel investors” offering ludicrous terms to startups that already don’t have many funding options.

At the very early stages of your startup, don’t be surprised if a Tunisian investor proposes a $10K check in exchange for 30% equity. The dearth of early-stage, local Tunisian investors makes it hard for Tunisian startups to raise their first round. The only bright spot in this landscape is the Tunisian diaspora. The quasi-entirety of good Tunisian angels are based abroad, sporting relevant startup and tech experience.

Exile to scale: the inevitable dilemma

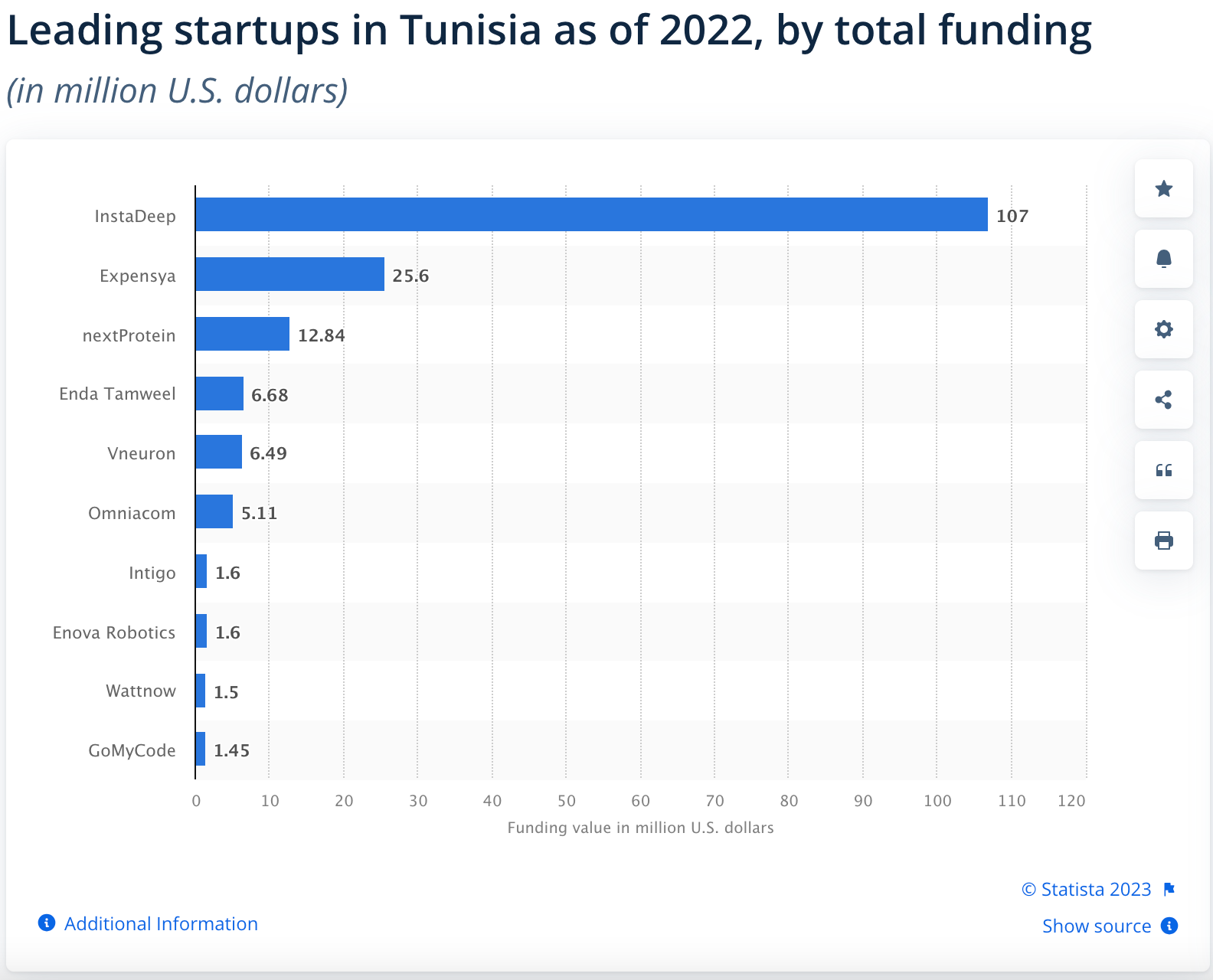

Instadeep. Expensya. Gomycode. Kaoun. All of those startups share two common traits. First, they are amongst the most successful Tunisian startups to date. Second, they are all incorporated abroad.

In the event that a Tunisian founder manages to raise money from angels and successfully test their product in the Tunisian market, they will be faced with another dilemma as they eye a potential Series A: the inevitability of exile.

Despite the much-touted Startup Act, which does represent a clear legislative improvement for the Tunisian startup scene, Tunisian regulations are still far too cumbersome to keep the best Tunisian founders in Tunisia.

Local stock options regulation is lackluster, a severe impediment to hiring the best talent. Services such as Stripe do not function in Tunisia. Until recently (this should change with the Startup Act’s much-awaited update), Tunisian startups were limited in the amount of foreign currency they could spend.

This last point proved to be a particular pain for inherently global tech startups, which rely on SaaS products and APIs from around the globe. Most of those services need to be paid in $ when a Tunisian startup’s revenue comes in the form of weak Tunisian dinars. This creates a double-whammy: not only is Tunisian startups’ purchasing power feeble internationally, but the very fact of buying internationally is hindered by foreign currency controls.

All of these factors converge to make “administrative exile” necessary for any Tunisian startup that’s achieved Series A level. While these startups still contribute to the Tunisian startup ecosystem by having teams in Tunisia, their potential impact on the ecosystem is clearly watered down by the fact they are based elsewhere.

Growing pains

All of my previous remarks are all tough love for an ecosystem I truly want to see succeed. My personal theory is that the Tunisian ecosystem is going through an “organization phase”, and that the rapidity with which the local startup scene grew led to a plethora of initiatives all at once, and a number of inapt actors took advantage of them.

The ecosystem now has to go through a “maturing” phase, weeding out the actors that don’t bring value to the ecosystem, reforming the Startup Act, and pragmatically viewing the Tunisian market for what it is: (at least in the context of VC-backable startups): a test market.

In order to get up to speed with the needs of Tunisian startups, local Tunisian banks should also start participating. As of now, the Tunisian banking ecosystem is hostile to startups, combining arduous bank account opening procedures and a complete absence of available financing options.

For French speakers

Conclusion

The Tunisian startup ecosystem has taken away too much from me during the 6 years I operated in it. While the talent and opportunity are there, I feel like I would be shooting myself in the foot if I spend the entirety of my youth here. When I’m 50 and successful, I’ll come back and invest in startups back home, by patriotism. But right now, the barriers to progress imposed by my country make it nonsensical for me to stay.

I do think that the ecosystem is going in the right direction. The local startup situation has definitely improved since the Startup Act (established in 2018) but a lot of frustratingly straightforward problems remain unresolved. For all of those reasons as well as the ones enumerated in the article, I won’t be starting a company in Tunisia again anytime soon. I’m waiting to be convinced otherwise.

The Realistic Optimist’s work is provided for informational purposes only and should not be construed as legal, business, investment, or tax advice.